Mezcal Land, Oaxaca

2023

Nestled in the rugged terrain of Santa Catarina Minas, Lalocura is a palenque that pays homage to its namesake - the esteemed Mezcalero "Lalo" and the ancient art of "cura," meaning "to cure." As visitors approach the entrance, framed by towering agaves, the main office beckons with its rich history and time-honored distilling practices. Here, Lalo and his team share the secrets of their craft, passed down over four generations and a century of expertise. Lalocura stands as a testament to the medicinal properties of mezcal and the enduring legacy of Oaxacan tradition.

At Lalocura, nature takes center stage in every aspect of the distillery process. The palenque's unique approach involves an impressive array of animal and insect companions, including horses, ponies, goats, bats, and over 20 species of insects. During a well-deserved work break, Don Juanito showcases his impressive lasso skills in a lively game of "rodeo," as fellow mezcaleros cheer him on.

Under the searing sun, Joaquin and Theo take a leisurely stroll through the verdant fields of maguey plants, having driven from Valles Centrales to visit the renowned Lalocura distillery. Joaquin, a devoted patron of Lalocura, holds a deep appreciation for their impressive range of over 20 unique mezcal expressions, each aged to perfection in wooden barrels.

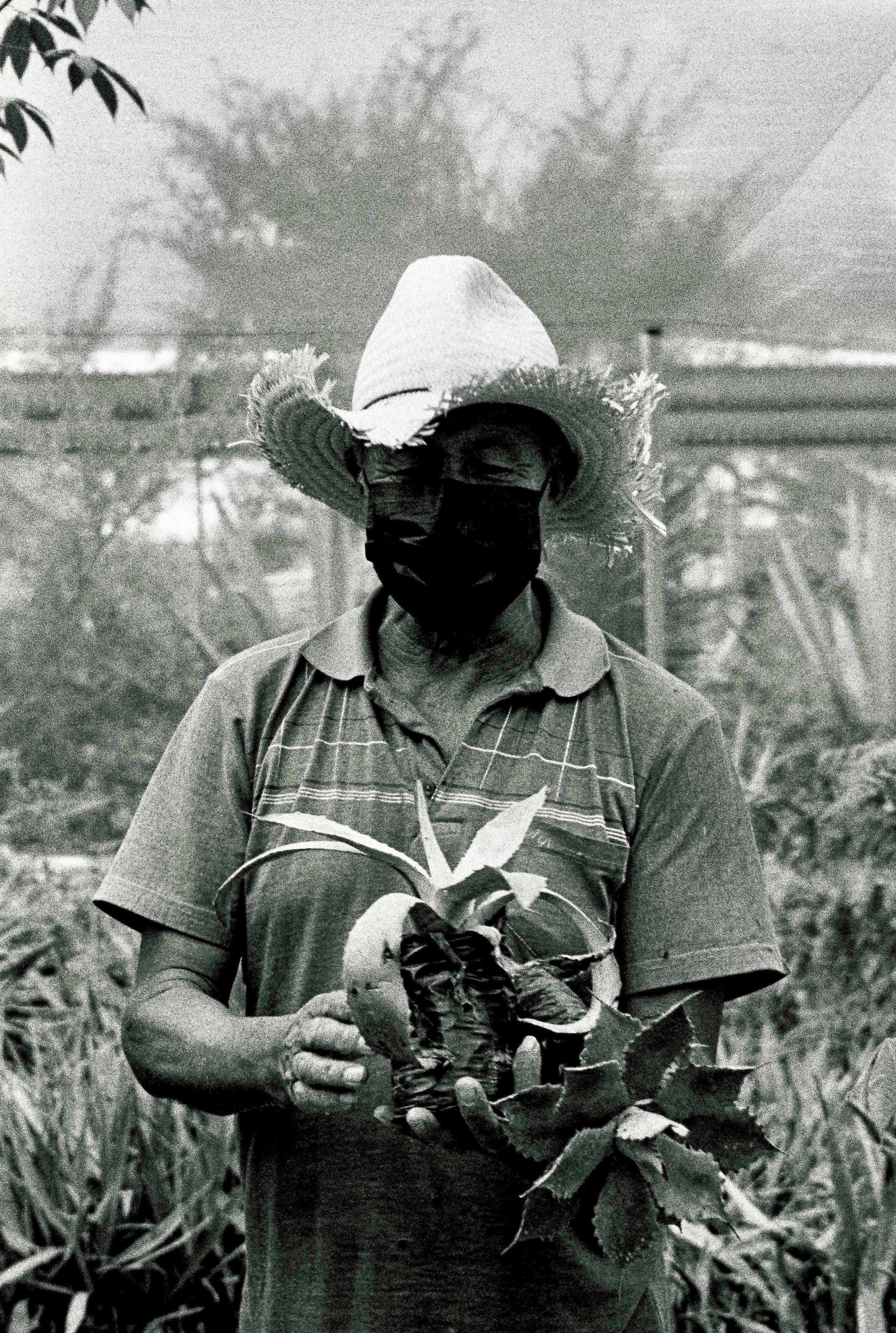

With skilled hands, master Mezcalero Lalo holds two precious hijuelos - little magueys that grow alongside their mother plant - one from a Tobalá Maguey and the other from an Arroqueño. As he explains the careful process of removing and transplanting these young shoots to ensure the continued health and vitality of the mother plant, Lalo speaks to the deeply personal connection he feels to his craft. "When I make mezcal," he reflects, "I express who I am as an individual, and the place from where I come. Mezcal is not a trend, it is history, it is heritage, it is wisdom, it is love."

Nestled amidst a field of mounds of wilted and dried agave leaves, a sturdy pickup truck stands guard, bearing witness to the meticulous process of mezcal production. At Lalocura, ancient Zapotec ovens use river stones that are heated over a wood fire until they glow red-hot. Once the stones are sufficiently heated, they are placed at the bottom of a conical pit dug into the earth, and the hearts of the maguey plant are piled on top. The pit is then covered with layers of agave leaves and earth, creating an oven that traps the heat and smoke inside. Over several days, the heat and smoke work their magic, wilting and drying the agave leaves to form a protective layer over the agave hearts cooking inside. This layer of leaves also infuses the hearts with flavor and moisture.

Two goats peer out of their pen, basking in the warm Oaxacan sun. Goats are integral to the mezcal production at Lalocura. In a nod to ancient tradition, the palenque uses tepetate, or goat dung, as a natural fertilizer for the agave plants and as a source of fuel for the ovens used to cook the agave hearts. By doing so, Lalocura honors the time-honored practices of the region's forebears, which recognize the intimate connection between the land, the animals, and the people who have made their home here for generations.

In the fields of Lalocura, the Agave Americana, also known as the century plant, stands out among the other species of maguey. Though it is not used to produce mezcal due to its slow maturation and low sap yield, it is highly valued for its unique qualities. The plant is cultivated for decorative purposes and to produce henequen, a durable and versatile material derived from the plant's leaves. Henequen is prized for its strength, moisture resistance, and the ease with which it can be dyed and finished, making it an essential component in the production of belts and other goods.

Amidst the rolling hills of Oaxaca, stands a colonial-era hacienda that dates back to the 17th century, bearing witness to the region's complex and tumultuous past. Once the property of wealthy Spanish colonizers, the hacienda was worked by indigenous and mestizo laborers who toiled under harsh conditions. After Mexico gained its independence in the 19th century, the hacienda system began to decline, and the sprawling property fell into disuse. Today, the old hacienda has been restored and repurposed as a restaurant and Mezcal tasting room.